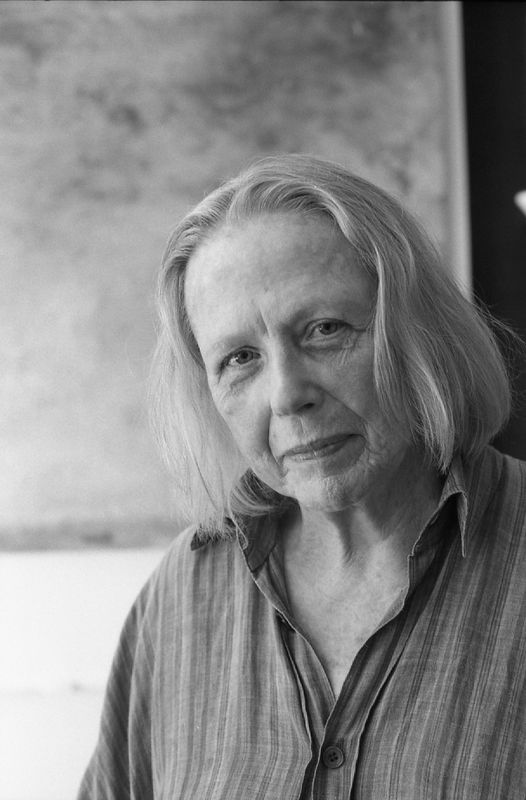

Katie van Scherpenberg Brazilian, 1940-2025

Born in São Paulo to European parents (her father Pieter was a naturalized Dutch citizen from Germany and her mother Mildred was Norwegian) in 1940, Katie van Scherpenberg soon moved to the US, then Canada, finally settling in London, where she lived until 1945.

Scherpenberg’s formative years were spent between Brazil and Europe, completing her studies in England, and a two-year scholarship granted by the German government in 1961-63 allowed her to study painting in Munich with Georg Brenninger (1909-1988) and in Salzburg with Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980). Scherpenberg returned to Rio de Janeiro in 1964, one week after the military coup that installed a dictatorial regime that would remain in power for the next two decades.

From the age of 26 to 33, she lived in her family's house on Santana Island, in the Amazon River delta, in the state of Amapá. There, the lack of professional art materials drove her to research ways to make natural pigments from soil. About this period in her life, the artist recounts: “You could say that the river was, among other things, so much paint, for it contained a large quantity of pigments (ferrous oxides) from faraway places, and together with this paint it brought me a whole lot of information. In this sense, the river is somewhat like a painting… A river is like life, it is never stable, by its very nature – particularly the Amazon.”

From 1973 onward, she established herself permanently in Rio de Janeiro. She began teaching at the Escola de Artes Visuais do Parque Lage in 1975, the year the institution was founded. She remained there for nearly three decades, coordinating the painting department and mentoring different generations of artists.

The 1980s marked the expansion of Scherpenberg’s paintings into outdoor spaces. In 1986, she created the iconic work Jardim Vermelho (Red Garden), in which she covered the grass in front of the Parque Lage mansion with iron oxide pigment. This intervention introduced the concept of landscape painting in Brazil and aligned with broader debates around land art and performance. Since then, she has carried out other remarkable interventions, such as Menarca (2007), in which, according to the artist herself, she “decided to paint the water and placed iron oxide directly into the sea, using the water as a canvas.” Works like Esperando Papai (Waiting for Daddy, 2004), Jardim Vermelho (Red Garden, 1986), and Furo (2001) meditate on geography, ancestry, and memory across the artist’s life.

In the early 1980s, alongside her practice, Scherpenberg worked on a project commissioned by the National Foundation for the Arts (FUNARTE) with the aim of developing good-quality art materials for the Brazilian market, which involved the analysis of mineral pigments from Brazilian soil that could be used to produce paints. At the time, artists could not access high-quality paints due to exorbitant tax import duties and a lack of interest from Brazilian industries in developing products for this niche market. This not only provided the artist with the opportunity to expand her research on local materials initiated in the Amazon territory but also opened up new possibilities to explore materiality in her own work.

From 1993 onward, the artist began the series of paintings entitled Feuerbach, in which she examines, deconstructs, and reenacts a landscape by the German painter Anselm Feuerbach (1829-1880), inherited from her father. Spanning over two decades, the production of these works involved the use of distinct chemical reagents such as salt, vinegar, and urine, applied to thin sheets of metal (copper or silver) adhered to the canvas, among other experiments. Inspired by the cracks and stains present in the 19th-century painting, the artist sought to examine, in her canvases, the effects of oxidation and material degeneration in the formation of an image.

Similar procedures are carried out in the series Mamãe, prometo ser feliz (Mummy, I Promise to Be Happy), produced from 1999 onward. In this series, Scherpenberg applies linens and bed sheets from a marriage trousseau onto the surface of the painting. Referencing the domestic and family environment, the delicately embroidered fabrics are profaned in these works. According to the artist, the inspiration for this series stems from a set of reflections on the importance of embroidery in the early history of painting, the identity and the role of women in a patriarchal society, and the artist's action between the visible and the subjective.

In 2022, Katie van Scherpenberg presented the installation exhibition Yakecan at the Cavalariças of Parque Lage, her most recent and unprecedented project. In Tupi-Guarani, the title means "the sound of the sky" and was chosen in line with the warning signal she sought to emit: forests are burning at a relentless pace. The installation was an extension of the intervention Síntese [Synthesis], carried out by Scherpenberg in the Rio Negro, in Amazonas, in 2004. On that occasion, the artist created five squares with white salt on the black sand at the river's edge, examining the relationship between these colors. However, the development of the work was entirely unexpected: “As the tide rose, it brought small charred wood fragments that settled on the salt. I understood it as a warning from the Rio Negro, which, in its own way, was already clearly denouncing the forest fires,” said the artist in a statement.

During the 1970s, Scherpenberg started to exhibit widely and won the prestigious Modern Art National Salon prize in 1976. In the 1980s, she participated in two São Paulo Biennials, presenting the series Kronos at the XVI São Paulo Bienal in 1981 and The Via Sacra at the XX São Paulo Bienal in 1989. Among her recent notable exhibitions are Traces: 1968–2007 (Cecilia Brunson Projects, London, 2023), Yakecan (Parque Lage, Rio de Janeiro, 2022), and Olamapá (Centro Cultural Oi Futuro, Rio de Janeiro, 2019).

Her work is part of significant national and international public collections, such as: Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, Texas; Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Collection, New York; University of Essex Collection of Latin American Art (ESCALA), Essex, UK; Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro – MAM Rio; Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo – MAC USP; Museu de Arte de Brasília – MAB.

-

Katie van Scherpenberg: the body of the work

Critical essay: Fernanda Morse 27 Mar - 24 May 2025 Galatea Padre João ManuelLosing Sight of All but the Body: Illuminations on K.V.S. Fernanda Morse * The artist Katie Van Scherpenberg never left childhood: she examines materials like a child discovering touch; relates...Read more -

Smoldering coals

Curated by: Tomás Toledo 27 Mar - 24 May 2025 Galatea Oscar FreireI know, the scars speak and the words silence what I haven’t forgotten[1] The desire to create this exhibition arose from my affection for the song Fera ferida [Wounded Beast]...Read more