Dani Cavalier: Solid Paintings

WEAVING ONE’S OWN DESTINY

Isabel Carvalho

Act 1: Oracular Opening

“When we wake up in the morning we are inspired to do some certain things and we do it.”

— Agnes Martin[1]

We know that every artist has their own ritual or habit that shapes the daily rhythm of creation—whether it is inventing an environment that fosters connection with what they believe in, or simply remaining in stillness until something reveals itself and the work takes form in their hands.

In her daily ritual, guided by the spirits of the gypsy Sara and Maria Conga D'Angola, Dani Cavalier lights candles, puts on a playlist, and turns to her oracles: a book by the Canadian artist Agnes Martin and the studio floor. For her, the process takes place when she reaches a state of presence in which the work unfolds unconsciously, even though it is steeped in concept. The floor is entirely covered in layers of colorful fabric, so she walks across it barefoot. And the fabric is not just any fabric—it is lycra. Stretchy, synthetic, and durable. For the artist, choosing each piece that makes up the work is like a roll of the dice—chance determines each piece’s place in the composition.

This text is divided into sections I call “oracular acts.” Each one explores a path traced by the artist—her references, questions, choices, and revelations. The latter emerge as a kind of guide (or oracle) for understanding the development of Cavalier’s work and the research around her Solid Paintings. Each oracular act begins with a sentence by Agnes Martin which, in some ways, anticipates the discussion that follows.

Act 2: Her Aunt’s Studio

“Do not think [inspiration] is reserved for a few or anything like that.”

— Agnes Martin

In many cultures, there is a historical association between women and textile practices. In some contexts, this connection encompasses all stages of production—from sowing and shearing to the creation of the final piece. This ancestral relationship has taken on different meanings depending on social class: for elite women, it was often used as a tool of domestication; for those in less privileged conditions, it became a survival strategy.

Nonetheless, it is important to consider how the stereotypes that link women to manual labor deemed “inferior” or “decorative” contribute to reducing their work to something “eternally feminine.”[2] This homogenizing view erases the variations, inventions, and specific contexts in which these women have operated. In the construction of hegemonic art history—shaped by men over the centuries—this framing has promoted the systematic devaluation of women’s work by standardizing their creative processes. Added to this is the imposition of hierarchies that relegate everything outside the consecrated realm of fine arts to a position of inferiority.

How has this construct affected—and how does it still affect—women who dedicate themselves to manual practices?

In one of our conversations, Cavalier shared that her interest in the creative field began in childhood, through contact with what she called “masked studios”—spaces she frequented regularly that, because they were occupied by women, were not recognized as artistic. Although she was unconsciously influenced by the creative process of her aunt—who made party decorations in her studio in Ilha do Governador, Rio de Janeiro[3]—she also absorbed, from her family environment, the idea that women’s work was tied to a process of erasure and the devaluation of technical knowledge not acquired through the study of art history.

Wishing to build a new reality for herself and for all women, the artist realized she could do something beyond the “masked studio” of her childhood, recognizing the political and transformative potential of textiles. Regarding the issue of women, textiles, and political resistance, Julia Bryan-Wilson highlights the example of the suffragettes who sewed and embroidered banners to take to the streets and demand their rights in the 19th century. Drawing on Rozsika Parker’s work, Bryan-Wilson underscores the matrilineal relationship of textile practices as a site for the production of “a set of knowledges that can be utilized for alternative purposes.” [4] If, on the one hand, women were educated for a feminine ideal, on the other, this knowledge also became a weapon of resistance.

Act 3: Bikinis

“When your eyes are open you see beauty in anything.”

— Agnes Martin

In 2015, alongside her studies in contemporary art, Cavalier launched a bikini production project with the brand Aro. This would mark her first encounter with materiality—an experience that would eventually lead to the development of the concerns present in her Solid Paintings. Her trajectory centers on two aspects related to women's histories and the sexist structures that continue to shape our society today. First, there is a questioning of the invisibility of manual labor; second, the need to develop a political act through clothing. In this way, the lycra bikinis she produced carry not only a material memory—lycra was created in the late 1950s to replace the rubber used in women’s girdles—but also the compression of female bodies within imposed beauty standards. According to the artist, the bikini is “the only category of clothing we choose for our own pleasure.”

Driven by the desire to engage with women more directly—addressing both the practice of manual production and the pursuit of female autonomy—Cavalier created the work Biquíni.pdf. In a manifesto published on November 6, 2023, she proposed “reclaiming autonomy” by making available a downloadable pattern for “a bikini pattern printable on standard A4 paper” and assembled according to the instructions provided, without any need for sewing. She also drew a parallel with Hélio Oiticica’s Parangolés, in which the act of wearing by the viewer activates the artwork and turns them into a co-creator. The result is an experience that reimagines our relationship to consumption and to the creation of art.

The artist also organized gatherings she called “factions,” where participants met in her studio to make the bikinis. No prior sewing or pattern-making skills were required—just a desire to rethink one’s place in the creative process and in the course of one’s life. This work can be compared to online tutorial videos that teach textile practices or other forms of manual production. It is a collaborative process that encourages autonomy and the sharing of skills that are often passed down from mother to daughter.

General notions about the connection between women and handwork—such as the textile practices mentioned here—often overlook the pleasure involved in these gestures and the encounters they foster among women. As Lucy Lippard observes, in recent decades we have witnessed a resurgence of “our mothers’, and aunts’ and grandmothers’ activities—not only in the well-publicized areas of quilts and textiles, but also in the more random and freer area of transformational rehabilitation.”[5]

Many of these practices involve reusing leftover or discarded materials—what Miriam Schapiro and Melissa Meyer call femmage. In this process, the creators perform an “archaeological reconstruction”, in which “collected, saved, and combined materials represented for such women acts of pride, desperation, and necessity. Spiritual survival depended on the harboring of memories.”[6] According to the authors, each repurposed scrap of fabric, bead, or button was a reminder of that woman’s life—where she lived, when, what she felt, and so on.

Women have long used remnants and scraps as a form of language, yet this practice continues to be dismissed as a legitimate form of art. As a result, much of what was produced in this way has been lost—while many so-called “discoveries” of modern art, such as collage, continue to be celebrated today as male acts of genius. One striking example of a woman artist belatedly receiving recognition is Madalena dos Santos Reinbolt. In her work, she “used materials discarded by the people in the households where she worked, relying on fabric remnants, scraps, and leftovers.”[7] In her case, the lack of access to conventional art materials—paint, canvas, brushes—drove her to create “wool paintings” as a way to express her creative impulse. Reinbolt’s pieces, like the work of so many other women who repurpose materials, are not only innovative but also speak to sustainability—a theme of great relevance today.

Dani Cavalier’s Solid Paintings can be placed within this same lineage: the lycra used to make them originates from textile industry waste. Through her practice, these scraps are elevated to the realm of visual arts. In doing so, Cavalier’s work fills the gaps in a history that has long privileged male creation, for male audiences, under a gaze that controls the female body and reduces women’s production to disposable objects.

Act 4: Solid Paintings

“There is the work in our minds, the work in hour hands and the work as a result.”

— Agnes Martin

There have been many attempts to rethink traditional painting, and one such effort was abstraction. Although there are ongoing debates about its “invention,” this is not the place to delve into that discussion in detail. Still, within the hegemonic art history, there is a prevailing consensus that certain male painters—among them, Wassily Kandinsky—were the pioneers of this new language. It has long been known, however, that women artists, such as the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint, were also experimenting with abstraction at the time. While the origins of abstract art cannot be determined with precision, modernist art history has often overlooked women’s achievements in favor of male figures. As a result, abstraction was for a long time regarded as a language developed by men.

Something similar happened with Abstract Expressionism which, despite including numerous women artists—such as Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler—was promoted as a predominantly male movement, with figures like Pollock, Rothko, and Newman brought to the forefront. According to Gwen Chanzit, curator of the exhibition Women of Abstract Expressionism, which took place at the Denver Art Museum in 2016, “[the] heroic machismospirit [..] has become a defining characteristic of the expansive, gestural paintings of Abstract Expressionism.” [8] In contrast, in Concrete, Neo-Concrete, and other post–World War II abstract movements—especially in Latin America—women artists began to gain prominence, such as Lygia Clark and Lygia Pape. In the 1970s, the feminist art movement also began to question the place of women in abstraction, both in painting and in Minimalist works: rejecting Minimalism, for example, became part of feminist practices at the time. “It stood, to us who were participants in what was called the ‘women’s movement in art,’ for the rejection of a kind of intellectual oppression that we felt neither accepted us nor gave us a chance to express ourselves,” observed Linda Nochlin.[9]

For Cavalier, painting remains rooted in “masculine frameworks”, which lead to the continued devaluation of women in the art market. In 2023, Artsy’s report on 2022 auctions revealed stark gender disparities, with women representing only 9% of total sales. The 2024 report,[10] based exclusively on Artsy’s own data, showed that 71% of searches on the platform in the previous year were for works by men, 25% for works by women, and 4% for non-binary artists, collectives, or artists with unspecified gender. Despite some progress in the visibility of women’s work, the report emphasizes that male artists continue to dominate the market.

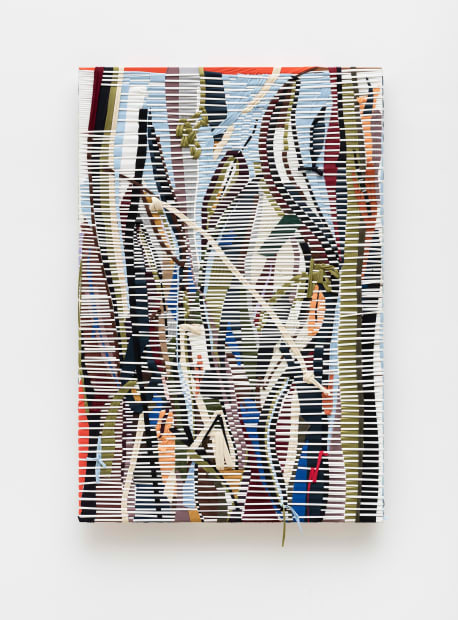

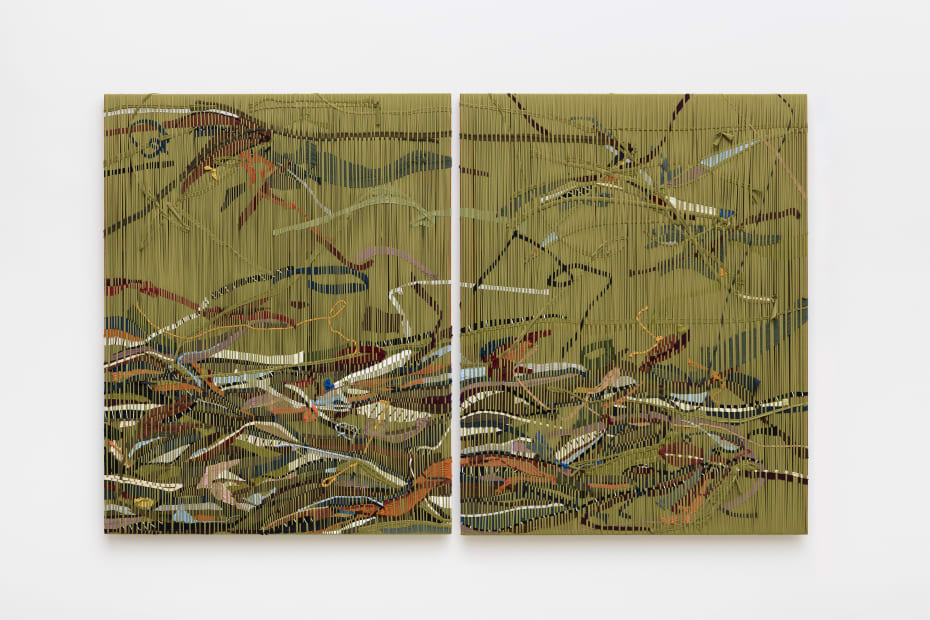

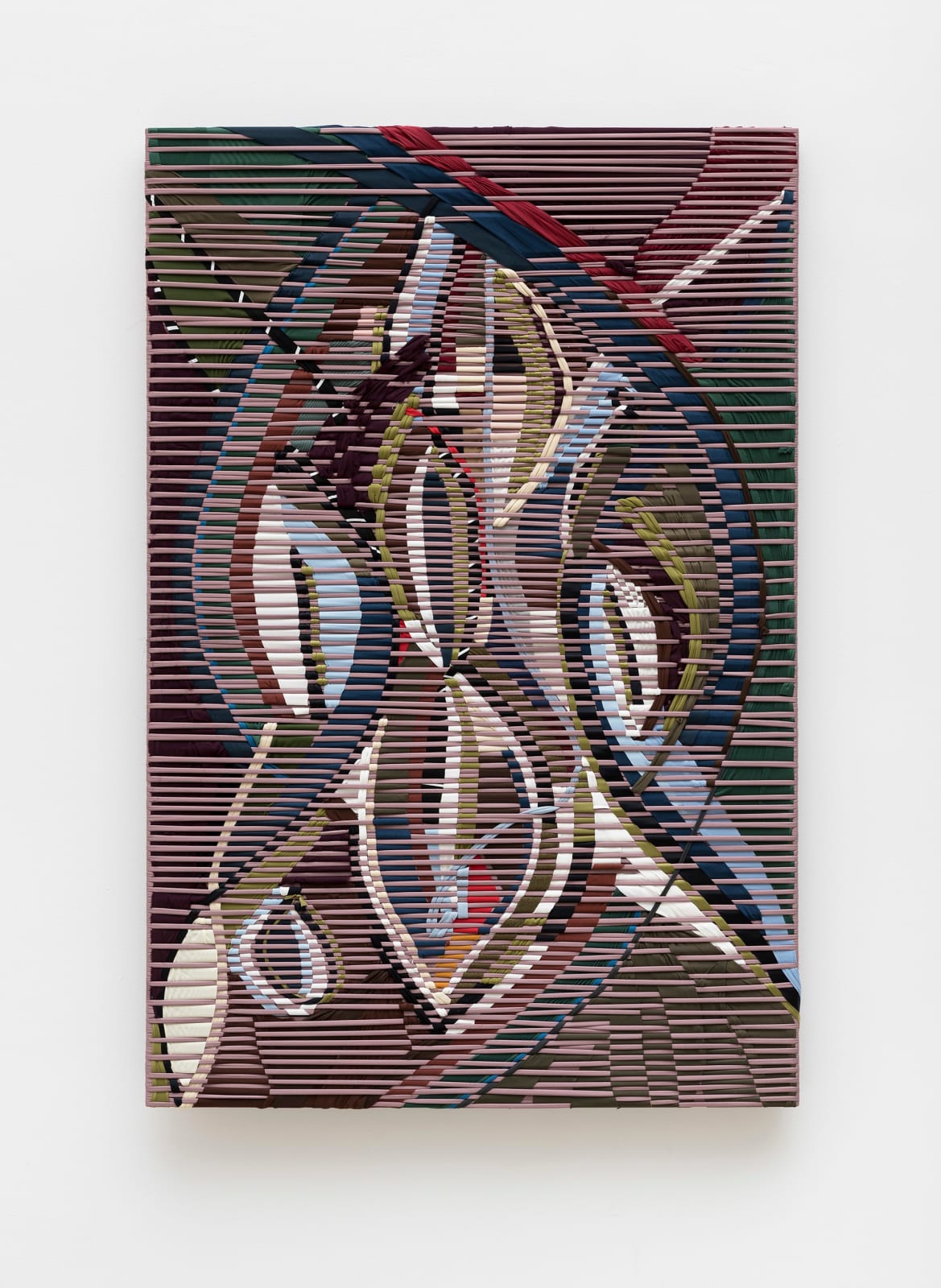

In response, Cavalier proposes what she calls “a debate within form”, transforming textile practice and painting into a space for reflecting on sexism in art history. It was in this spirit that she began her first Solid Paintings, draping and stapling lycra. A Solid Painting is, therefore, a language and technique developed by the artist that neither rejects painting nor abstraction but proposes a new way to understand and resist the issues she identifies. In the series As Pensadoras [The Thinkers] (2025), composed of monochromatic works, Cavalier emphasises the place of women within painting and textile art as an established artistic language, while also questioning the genius attributed to the authors of the most revered monochromes in art history, such as Kazimir Malevich and Yves Klein. The act of stitching the lycra reveals its texture and, with it, the textile path of Cavalier’s creative process—and that of other women. More than simply using their hands, these women create from lived experience, thought, and necessity.

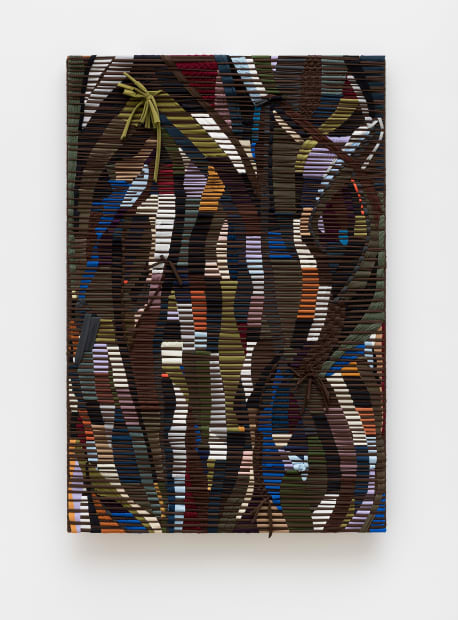

Cavalier’s work often references women’s creative processes—both directly and indirectly. This is evident in Três Marias [Three Marias] (2025), in which pieces of lycra tied to parallel threads extend beyond the edges of the frame, creating a three-dimensional texture that recalls the lycra rugs made by women from fabric scraps and sold by the roadside in Brazil. For the artist, the stars of the work are the three Marias who protect her: Maria Conga, Maria Mulambo, and her grandmother Maria, who was a seamstress.

Like a constellation, each Solid Painting carries mythologies and takes form through the gathering of lycra threads—its stars—pulled from the ever-growing heap on the floor. The first layer of spun lycra is stretched tightly across the frame—each one custom-built to withstand the tension without giving in. This base then serves as the support for stitching on other layers of spun lycra. Spinning, in fact, is a central stage of the process, typically done when, according to the artist, she wants “to think.” It is a mechanical action that is fundamental to textile work: the creation of the thread that will give meaning and life to the piece. The threads also chart their own course. So even though the artist seeks to maintain control, the works are also shaped by chance—the creative process’s own “roll of the dice.” In selecting the spun lycra pieces from the floor, in a kind of oracular practice, Cavalier performs what she calls the “color catch.”

Her work is guided by a clear intention to subvert the values historically assigned to women’s presence in art and to build memory through manual making. But there is also intuition: each piece is born from a particular state of mind. Her works are “smoked,” she says, to create an atmosphere conducive to revelations. This is why the ritual in the studio—described at the beginning of this text—plays such a key role. Intention and intuition are woven throughout the artist’s visual practice, as she seeks to emphasize this relationship in the very structure of each piece.

When discussing the work of Agnes Martin—a major reference for Dani Cavalier—Catherine de Zegher observes that it “has been described as leading the viewer into contemplative spaces where the processes of making and viewing become fused.” [11] In Cavalier’s work, we can also perceive gesture, materiality, and the path of process. These are the lines that intersect in the stitching of the lycra, the shapes and textures that emerge, and the tension of the wooden frame.

The solidity of the Solid Paintings relates to two types of resistance: one that arises from the material tension of the lycra stretched over the wooden structure, and one that confronts the canons of painting and art more broadly. These works are at once tangible and contemplative. In front of them, the viewer can follow the steps of their making—through the arrangement of fabric cuts and the construction of the woven structure—while also being invited to reflect on the place of painting and of women in art history. When introducing the work E sou eu filha do vento [And I Am the Daughter of the Wind] (2025), Cavalier sang a line from the chant to the goddess Iansã that inspired the title: “as the daughter of the wind, the wind cannot knock me down.” A message that echoes the strength of her work.

Isabel Carvalho is an art historian and professor.

[1] All quotes by Agnes Martin were taken from the book Writings / Schriften, published by Hatje Cantz in 1998.

[2] Rozsika Parker. The Subversive Stitch. Londres: The Women's Press Ltd, 1996, p. 4.

[3] Cavalier lived in a two-story house with her parents upstairs and her aunt and grandmother lived downstairs. Her aunt's studio was located at the back of the house.

[4] Julia Bryan-Wilson, Fray: Art and Textile Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017, p. 9.

[5] Lucy Lippard, “Making Something from Nothing. (Toward a Definition of Women's Hobby Art”, Heresies, n. 4, 1978, pp. 62-65.

[6] Miriam Schapiro & Melissa Meyer, “Waste Not, Want Not: An Inquiry into what Women Saved and Assembled--FEMMAGE”, Heresies, n. 4, 1978, pp. 66-69.

[7] Julia Bryan-Wilson, Seguindo os fios de Madalena. São Paulo: MASP, 2022, pp. 50-75.

[8] Apud Sam Moore, “The Gender Trouble of Abstract Expressionism”, ArtReview, Jan. 2024.

[9] Maura Reilly, “A Dialogue with Linda Nochlin, the Maverick She”. In: Women Artists: The Linda Nochlin Reader. London: Thames & Hudson, pp. 11-54.

[10]Casey Lesser, “The Women Artists Market Report 2024”, Artsy, Mar. 2024.

[11] Catherine de Zegher, 3 x Abstraction: New Methods of Drawing by Hilma af Klint, Emma Kunz, and Agnes Martin. New York: The Drawing Center, 2005, pp. 23-40.