Regina Silveira: Tramadas: Critical essay: Ana Maria Maia

The hand is the reverse of the image

Although Regina Silveira has been engaged in nearly sixty years of research into graphic technologies, culminating in a conceptual and multimedia artistic trajectory, manual labor has never ceased to be a theme in her work. What might seem like a contradiction actually reveals her constant desire to understand the world through ambivalent encounters, both productive and conflictual, between structures and gestures—or collective agreements, laden with inherent mechanisms of power, and the horizon of use, expression and disobedience available to each individual in the face of such conventions.

Hands first became a theme when the artist was teaching printmaking and wanted to satirize an academic mindset that attempted to preserve in that medium a notion of authorship tied to gestural trace. From that point on, these limbs continued to appear in her work as a broader reminder that, whether handcrafted or industrial, everything that is given was once constructed as such. Therefore, before things are what they are, it is worth remembering that they were once someone’s idea and work, and the result of countless subsequent decisions that gave them meaning, function, relevance, and purpose. The polished surface of images, which Western history has led us to suspiciously apprehend as faithful evidence of reality, especially since the advent of photography, becomes the dogma the artist seeks to confront. With the intention of reflecting on a politics of representation, she turns her work into a continuous invitation for us to keep our gaze alert and inquisitive before the effectiveness of visual discourses that surround and so deeply shape our imagination.

These lessons have been explicit since the late 1970s, when Regina participated in a pioneering moment of video art in Brazil. During the civil-military dictatorship, an era when, not coincidentally, commercial television became popular in the country as the main mass media, her generation found in audiovisual language the resources to capture everyday images with technical precision and a countercultural bias.

Framed in close-up before a school blackboard, it is precisely the artist’s hands that take center stage in a series of video works[1] produced in the context of the Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo (MAC USP). Through simple and prescriptive movements, this fragment of the body preserves the anonymity of gesture while emphasizing the didactics of subversion. In Campo[Domain](1977), the index finger slides along the edges of the image to point out its limits and suggest what escapes them. In Artifício[Artifice], from the same year, the fist grabs the translucent end of an adhesive tape on which the title of the work is written, making it disappear in seconds, along with the illusion of its existence as anything more than a mere imagetic phenomenon.

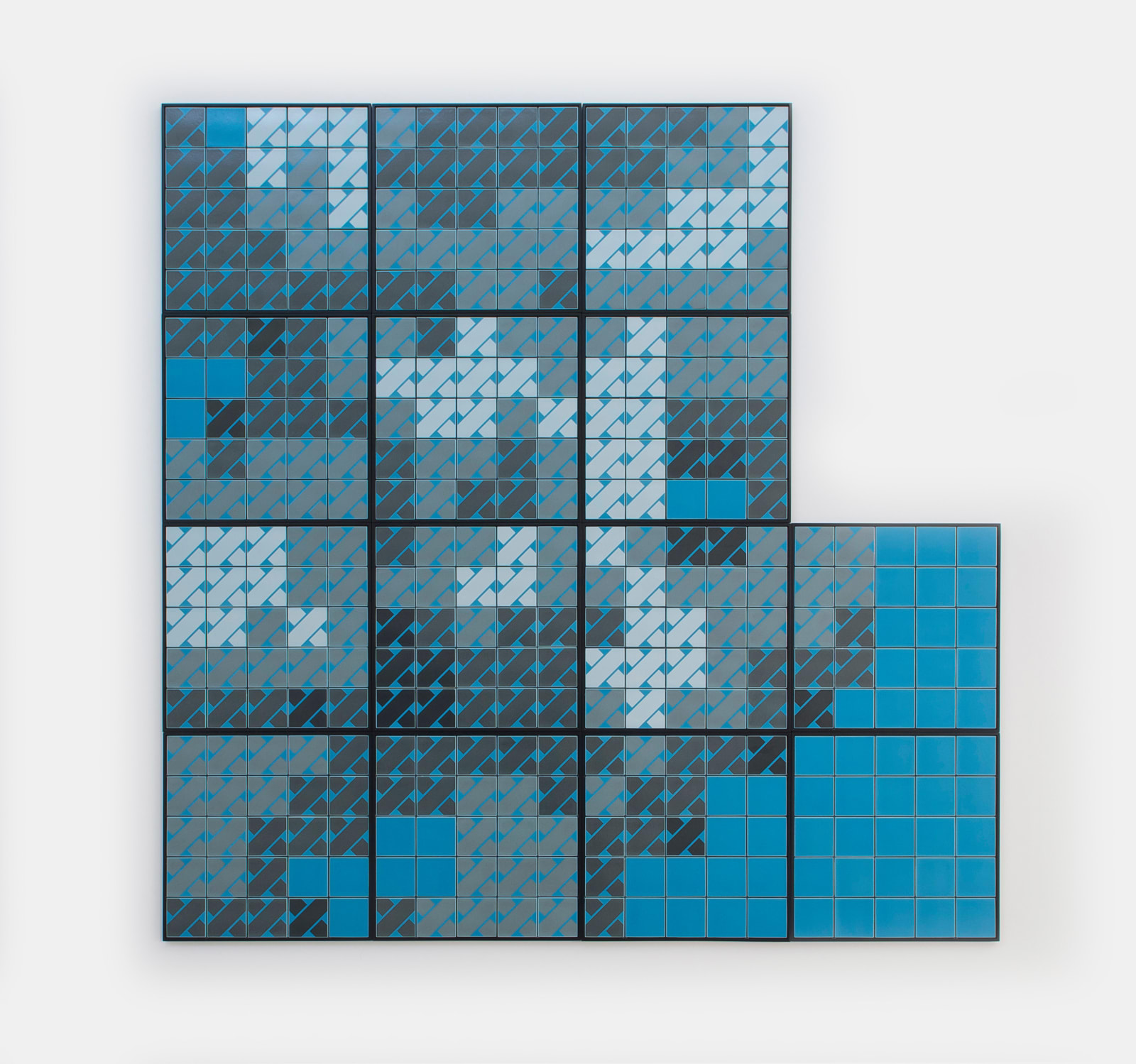

The same hands that uncover hegemonic narratives are those that remain restless as the artist weaves her own paths through life and work. Her current solo exhibition at Galatea Salvador gathers pieces from various series and actions created since the 1990s, across different mediums. Printmaking, lito-offset, silkscreen on paper or utilitarian objects, digital printing, tile work, vinyl cutouts, and urban interventions form the vocabulary on display, while also pointing to a career consistently marked by deep research into materials and languages, ranging from the most traditional to those emerging from contemporary experimentalism. All selected projects refer to the practice of embroidery, employed not only as a compositional method, but even more as a metaphor for manual labor, material culture, and a doctrinal education commonly associated with the female gender and domesticity.

By taking on this practice and the social preconceptions associated with it, Regina begins to embroider. On gridded weaves, she places each stitch with an interest in both composing images and investigating their codes. Needles, skeins of thread, thimbles, pins, scissors, and buttons continue to form a universe of tools and themes, somehow disrupted by the presence of other tools for cutting and construction, such as a bottle opener and a screw in the series Risco[Risk] (1999), or a revolver and hammer in Tramada[Woven] (2015). To ignore their differing functions and implicate them in the same embroidery is a procedure that must be highlighted as an important aspect of the artist’s commentary. Representing them is a second crucial step, allowing for an analytical approach to visual statements. As in the Kosuthian[2] equation, this body of work continually proposes relationships between tools, objects, and images, triggering a play of translations and synonymies that links the thing itself to its potential qualities or to its traces as memory.

In Tramada (pink) [Woven (pink)] (2014), a geometric composition emerges from diagonal cross-stitch embroidery. The piece spreads across nearly the entire surface of a large support, leaving few visible reference points. A needle pierces the lower corner, as if the activity had been paused. It seems the creative process could resume, if not for the fact that the moment was photographed, thereby extracting any possibility of future movement from the image. There is something melancholic—and precisely because of that, powerful—in the realization that many of the political and aesthetic insurgencies Regina Silveira prescribes end up confined once again within the realm of technical images.

The artist does not seem to reject this fate; rather, she seeks to understand it by acting as a kind of infiltrator. She appropriates structures of industrial production, embracing their reproducibility and optimization strategies, and constructs a persuasive visuality that can coexist with, and at times blend into, the languages of graphic design and advertising. In this way, she comes very close to the core of the “imagosphere”,[3] the current system of hypermediation and control over life experiences and social relations through images. She implicates herself in this regime of visibility in order to challenge its paradigms, creating presences that speak much more of absences.

Shadows and traps

By varying angles of observation and light over the objects she represents, Regina Silveira distorts their forms and provokes long shadows that stretch across the surrounding space. This is a strategy the artist has been exploring since the 1980s in both installation[4] and two-dimensional works. In the Armarinhos[Notions]series (2002), the shadows stem from notions of haberdashery, whose triviality suddenly gives way to mystery, while their small scale begins to encompass an immense dimension. The dark stain that steals the spotlight in these works fuels the belief that everything has a soul, even a simple needle. Thus, while stirring the imagination, the graphic element also challenges the notion of a single and stable objectivity, pointing instead to the irreducible place of subjectivities.

The artist’s trajectory suggests a consistent effort to empower individual agency. This is evident in her attempts to unmask and liberate everyday life within the private sphere. It also appears in projects for public space, where she confronts the norms of collective life and situates dreams and delirium within the realm of the possible. In 2010, when invited to intervene on the external architecture of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (Masp), Regina covered the entire glass façade with the image of a graphic sky. In the vision of Tramazul[Blue weave], the atmospheric landscape was not above the building, as usual, but on it. The sky drew nearer to visitors and revealed itself as the unfinished product of human labor. Its weaves remained visible, and its clouds appeared as if still being embroidered by someone.

As she stitches across cities, Regina Silveira enters the debate about the consequences of the modern project of condensing spaces of life and sociability. The symbolism of her graphic weaves encompasses the flows and networks made possible by urbanity, amplifying the experience of those who inhabit these spaces. This dimension is evident in Casulo [Cocoon](2013), an intervention carried out on buses and bus stops in Curitiba’s transit system. Composed of oversized cross-stitch patterns applied to the ceilings and windows of these structures, the work also reveals the other side of such ambition. The image of a public facility enmeshed in stitching gestures toward the impossibility of truly accessing what the urban environment offers, due to the strength of political and economic powers that erect it and the real estate capital that increasingly besieges it. The loss of civil rights becomes the clearest sign of the failure of the city as a collective project.

If embroidery reveals both the utopias and the crises of worldly forms, then embroidering can serve as a useful exercise in uncovering the solutions and traps left along the way. Regina Silveira’s wager is to cross through this duality as if it might yield hypotheses about what is possible for art in relation to technique and the various institutions that organize ethics around knowledge and making.

Among the many possible answers, one emerges from Bordado malfeito[Badly made embroidery] (2025). This translucent panel greets visitors with a warning: freedom as principle and profanation as method. The artist’s hands do not appear in this work, nor in most others, but her disobedience makes her presence felt. With every crooked line or stitch that escapes the grid, she affirms her own rights, those of art, and those of women to be whatever they want to be, and to do whatever they want to do—with their feet grounded in history and their hearts and minds wherever their desires may lie. Humorous yet serious and forceful, the raised finger of insult or interdiction, projected as a rotating holograph in the video Una vez más[One more time](2012), reclaims the vocabulary of gesture without conceding a single inch of what has been won so far. The finger may not be physically on display, but its attitude is very much present in the imagination of the exhibition.

Ana Maria Maia

June 2025

[1]In 1977, Regina Silveira developed her first works in this language: Artifício [Artifice], Campo [Domain], and Objetoculto [Hidden Object], all created through language games between her hands and elements of a school setting associated with writing and illustration exercises. In 1980, the artist completed the work A arte de desenhar [The Art of Drawing], which shares characteristics very close to the initial series.

[2] In One and Three Chairs (1965), American artist Joseph Kosuth brought together three elements in an installation: a chair, the dictionary definition of that object, and a life-sized photograph of it. Placed side by side, these synonyms draw attention to how language mediates aesthetic experience and our perception of the world.

[3] Paul Weibel describes the “imagosphere” as something that “entirely covers the planet. [...] a continuous layer of images that interposes itself like a filter between the world and our eyes” Paul Weibel, “Electronic Culture in Ars Electronica Center”. In: Timothy Druchrey, Ars Electronica: Facing the Future. MIT Press: 1996, p. 227.

[4] In In Absentia (1981), an installation presented at the 16th São Paulo Biennial, the artist arranged two empty museum pedestals and, from them, painted the floor and walls to indicate the shadows of two works by Marcel Duchamp, a canonical figure of European modernism.

![Regina Silveira, Alfinete, da série [from the series] Armarinhos, 2002](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_1600,h_1600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/antoniabergamin/images/view/7e6c27d2c7b985e20d1a5ff326b8f0b4j/galatea-regina-silveira-alfinete-da-s-rie-from-the-series-armarinhos-2002.jpg)

![Regina Silveira, Martelo, da série [from the series] Tramada, 2015](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_1600,h_1600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/antoniabergamin/images/view/32ff3868b1ed7acb0909592cc219cdf3j/galatea-regina-silveira-martelo-da-s-rie-from-the-series-tramada-2015.jpg)