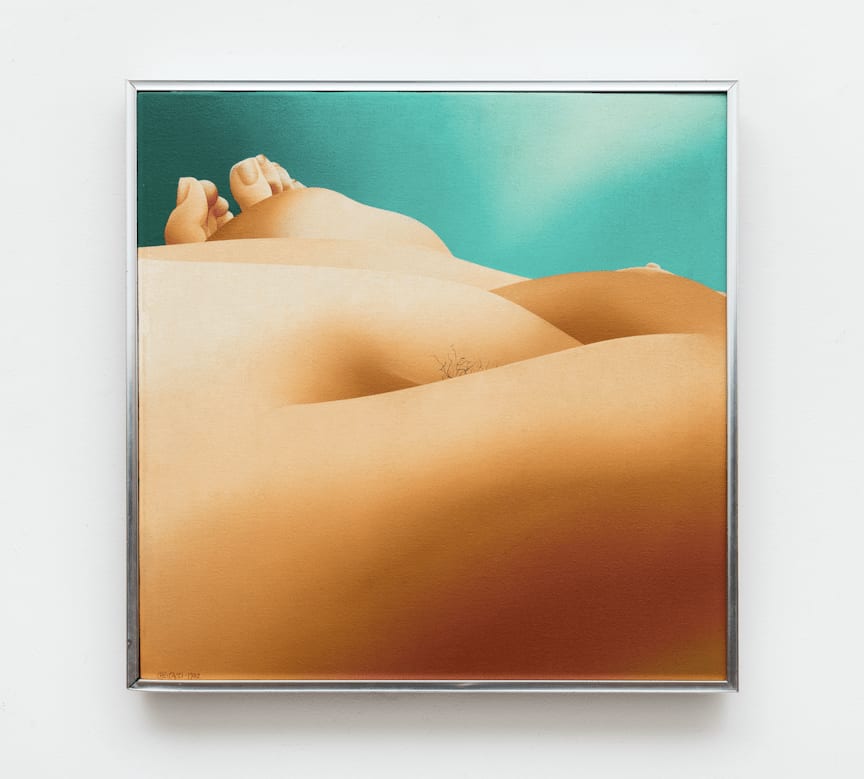

The body elevated to landscape

Fernanda Morse

“I consider all of my work in sequence. I have

always been concerned with the human figure.

I began with a group of people and then started using just one.

Continuing my search, I observed the details, which

I kept editing until reaching the hand and the feet.

I’ve been delimiting throughout maturity."

Pietrina Checcacci, A Gazeta, 11.27.1973

“Of the body. But what is the body?” one reads in the first lines of Ferreira Gullar’s Poema Sujo [Dirty Poem], written in 1975 during the poet’s period of exile. In the work, the physical body is placed into question, re-elaborated, and re-evaluated at a moment of fracture of the social body. How does this body, “this bone that I can’t see,” look and is looked upon in moments of tension and censorship? And how is it able to be so mysterious as a form, filled with folds and creases? The beginning of Pietrina Checcacci’s career witnessed the outbreak of the military dictatorship in Brazil, which did not go unnoticed in her work. If at first her interest in the human figure was manifested in the representation of groups of people, as mentioned in the epigraph, this approach was precisely concerned with the body in a social sphere. Over time, the artist moved in the direction of the poet’s question, delving into the minutiae of the human body—more specifically, the female body.

The works Sob o signo de câncer [Under the Sign of Cancer]and Família brasileira [Brazilian Family]from the series O povo brasileiro [The Brazilian People](1967-1968), known as “banners,” and the installation A novela [The Novella] (1965-1967) correspond, in turn, to the initial period of Checcacci's production, when the body is brought in its groupings, inserted into political life, reproduced in mass culture, and divided between games of appearance and moral conflicts. Here, the conversation with generational peers such as Rubens Gerchman in Não há vagas [There Are No Vacancies] (1965) and Anna Maria Maiolino in O herói [The Hero] (1966) is evident. The artist returns to this approach sixty years later with a series of "floating" works: Yes, nós temos bananas e outras cositas más (Yes, We Have Bananas and a Few Other Things) (2022) and Juntos e misturados (Together and Mixed) (2024)—pieces that, incidentally, bring something of Glauco Rodrigues, another exponent of painting in Rio de Janeiro in the 1960s.

In the transition to the 1970s, the human body began to be given the dimension of landscape. In a 1973 text, the art critic Roberto Pontual comments: “Pietrina titled a series of paintings Evaterra, where the skin of the body corresponds to the skin of the earth. With this, she proposed the subtlety of inverting an old principle: it was no longer the earth that was the source of the body, but the body that was presented as the matrix of the earth. The landscape was the body.” Paintings in the exhibition, such as Evaterra (1971), Carnações [Carnations](1982), and A doçura dos corpos [The Sweetness of Bodies](2011), show the continuity of this research. However, what is this body brought by Pietrina amidst its many uses and figurations that were established in Brazilian art concomitantly with the first years of her career? She who started at the Escola Nacional de Belas Artes studying painting and delving technically into this language that was widely questioned by certain artistic currents of the time, which in turn were much more interested in objects, the elements of the world, and the very action of the body over them than in its representation.

Pietrina’s dialogue with the pictorial tradition is also evident in titles such as Carnations. In visual arts vocabulary, the term refers to the representation of human skin. The way an artist develops carnation in their work was once so important that academic art criticism could use it as a criterion for evaluating their skills as a colorist. In Pietrina’s case, the transition between shades of orange, brown, ochre, and red brings density and expressivity to the parts of the body highlighted in the scene. The artist’s mastery over the nuances between these colors and the incidence of light is undeniable, as she creates a unique couleur chair that is much more suited to the temperature of the tropics, far removed from the pink predominant in the carnation of European painters. The term is also more specifically connected to the lexicon of sacred art and baroque statuary, referring to the process of reproducing, in a realistic and dramatic way, the effect of human flesh and skin in sculptures of biblical characters. This use of the word is of interest here as it contrasts with the sensuality and distortion of forms explored by Checcacci. The body, as a subject, is sacred in her work, but the thoroughness with which she unfolds it and shows it to the world is aligned with the sphere of profanation.

However, the erotic dimension of this skin that is displayed has often been denied by the artist.[1] A question of censorship, perhaps?[2] In any case, it was an aspect present in the paintings of many Brazilian artists active at the time, in line with demands for the recognition of women as desiring subjects brought about by the second wave of feminism that emerged in the United States in the 1960s. Women were then seen representing women's bodies in a multiplicity of forms hitherto unprecedented in Brazilian art—Wanda Pimentel, Teresinha Soares, and Regina Vater are prime examples of this turning point.[3] However, accepting this exercise in freedom was not so simple, as can also be inferred from the fact that Pietrina omitted her first name from the signatures of most of her works produced until a certain point in the 1970s, leaving only, Checcacci.[4]

Critics also perceive a diversity of references and dialogues in her work, as well as a connection with hyperrealism, which was on the rise at the same time. In interviews, she also denies a voluntary connection to this movement: "I'm not a hyperrealist either. I don't start from photography, but from sketching. I have nothing against hyperrealism, but I make a point of not being one.”[5] Because of the distortions caused by ultra-close details of the body, as well as compositions that unite decontextualized elements (the rope, the butterfly), she may be associated with certain approaches to surrealism, regarding which she comments: "I make a point of remaining in the real. I know I'm on a tightrope, very close to the surreal. But I'm attentive, observing the human being.”[6]

So, again, what is this human body of Pietrina’s? It is not the body of the abject,[7] the obscene,[8] and the formless,[9] to evoke the debate brought by the North American magazine October in the 1990s. It is not the same skin exposed to violence portrayed by Nan Goldin, nor Cindy Sherman’s pastiche body, nor the scatological matter of Andres Serrano. If the formless consists of the ruin of good form, if it seeks to "debase and put in disorder any taxonomy,"[10] the human body for Pietrina, even when placed in erotic tension, even when stripped of its noble parts (you see much more foot than head), it is a body that is elevated by art, or that her art wants to elevate.

[1] "My art is not erotic. A finger is just a finger." reads the headline of an interview published on 04.26.1975 in the newspaper Última hora.

[2] In her thesis "Feminist crossings: a panorama of women artists in Brazil in the 1960s and 1970s" (2018, p. 245), researcher Talita Trizoli comments on the fact that the reproduction of a work by Pietrina was censored when it was to be published in an article in Veja magazine in 1974.

[3] The recent exhibition "Women in the New Figuration: Body and Positioning", curated by Camila Bechelany and Gustavo Nóbrega, shows the strength of the transformation taking place at the time.

[4] Trizoli goes on to say: "Checcacci, for example, didn't agree to have her picture taken as a young woman for newspapers and other means of publicizing her work, for fear of being reduced to the stereotype of the 'young and beautiful artist', a stance that even extended to her signature on her works - she claims that she signed her works only with her surname, hiding her gender for fear of prejudice." (2018, p. 242).

[5] Diário de Notícias, 09.12.1974.

[6] O Estado de São Paulo, 12.8.1973.

[7] “This body is the primary site of the abject as well, a category of (non)being defined by Julia Kristeva as neither subject nor object, but before one is the first (before full separation from the mother) or after one is the second (as a corpse given over to objecthood).” Hal Foster in the essay "Obscene, Abject, Traumatic" published on October 78 (1996, p. 112)

[8] “Obscene" does not mean ‘against the scene,’ but it suggests an attack on the scene of representation, on the image-screen.” (Foster 1996, p.113)

[9] "In Bataille’s project, which he calls “atheological” or “scatalogical,” the informe is something like a first principle that defines what is excluded from Western metaphysics. The informe is understood as something that’s going to undo categories.” Yve-Alain Bois in the interview "Down and Dirty: “L’informe” at The Centre Georges Pompidou", Artforum, summer 1996, available at: https://www.artforum.com/features/down-and-dirty-linforme-at-the-centre-georges-pompidou-202066/

[10] "L'informe consists in declassifying, in the double sense of rabaisser, of putting disorder into every taxonomy, in order to annul the oppositions on which logical and catégorielle thinking is based. " Bataille apud Krauss and Bois in the introductory text to the exhibition L'informe : mode d'emploi, presented at the Centre Pompidou in 1996.